On Paths and Pauses

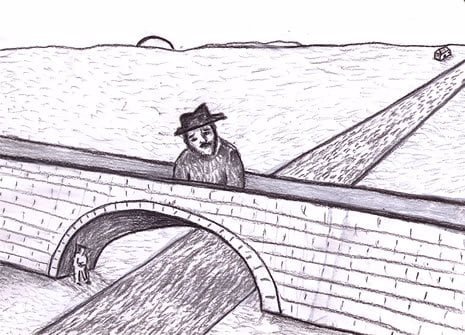

“The Story of Isaac Ben Yakil”, charcoal by David Asher Brook

Rabbis love stories about other rabbis, and stories about dreams, so here’s one with a little of both for this Yom Kippur evening.

Around 200 years ago, every new student of the famous Rabbi Simcha Bunam of Peshischa would gather around to hear him speak of Rabbi Itzik ben Yekel who lived in the Polish city of Cracow.

Rabbi Itzik was a faithful man though impoverished and long-suffering. He was also a dreamer. One day, he told his community of a new, amazing dream that had come to him in the night. In this dream, he walked down a magnificent bridge filled with intricate, imposing sculptures on either side. The bridge was bustling with untold numbers of people and horses, all on their way toward a great palace. At the end of the bridge, his gaze rested upon the muddy river bank. Placing his hands in the soft earth, he dug and dug for what felt like hours and pried open a wooden chest filled with glittering gold bars. The rabbi was overcome with emotion as he dreamed what this newfound wealth would bring his community. In that very moment, he awoke in his cold Cracow bedroom, wondering what it all meant.

This dream was so vivid in his mind. He couldn’t shake it all day as he struggled to focus on his Talmud study. What if this bridge and gold chest were real? What if they were sitting under the earthen shore somewhere, waiting to be found? Finally, he sheepishly told his friends. They laughed. He told his wife, Briendel. She smiled at him and kissed his forehead.

Yet the dream was not done with him yet. The following night it came and went again. He awoke and sat bolt upright in bed with a flash of a realization: The city is Prague! He woke up his wife.

“Briendel! I must go to Prague and see if this dream is true!”

“Itzik, you cannot be serious. That’s an awfully far way to go for a dream. There’s so much that needs doing here!”

He told his friends and once again they roared with laughter. “Itzik, why don’t you save yourself the weeklong schlep and just dig in my backyard. If you find gold you can keep it!”

And yet, the dream came once again for the third night running! This must be more than a coincidence! Itzik had never left Cracow in his life but he dutifully packed his bag and set forth for the long journey to Prague.

Finally he arrived in the grand city. There was the grand Charles Bridge, exactly as it had appeared in his dream! Although he had never before seen it with his awake eyes, he knew it immediately. He took up his shovel and went to start digging. Before he could set tool to ground he was stopped in his tracks by a tall, stern guard who watched over the bridge day and night.

Rabbi Itzik waited for an opportunity. He waited days that felt like lifetimes. There was always a guard on duty. Didn’t these giants need to eat or sleep? Wouldn’t they leave for a few moments, and then Itzik would have a chance to dig up his prize? Finally over time, the rabbi and the guard got to talking. They even shared a meal on the blustery bridge.

One evening the guard asked Itzik why he had made the long trek. Why did he care about this bridge so much? Fearing the scorn he had faced from his wife and friends, Itzik shyly told the guard about his dream. The guard laughed, “Following this dream, you wore out your shoes coming here to Prague? I don’t have that sort of faith in dreams! You won’t believe this, but one time I had a dream that told me to travel to Cracow and dig up the ground under a kitchen stove! In the house of a Jew named Itzik ben Yekel! But who could find such a person? I bet there are hundreds Itziks and Yekels, hah hah!”

The color ran from Itzik’s face and he fled from the bridge toward the closest donkey cart heading home. A week later, he burst through the doors of his home.

“Briendel! Help me move the stove!” They thrust the shovel into the earthen floor and hit something hard - a chest of gold! Using the money to start him in business, Itzik went on to become the most prominent merchant in Poland and funded a glorious synagogue in Cracow that is still known as Reb Itzik’s shul. I’ve been there. It’s a stunning building with early Baroque architecture, intricate Hebrew inscriptions decorating the walls, and hosts the most mediocre Kosher pizza store this side of the Volga.

Now as far as I know, this is a completely true story. If you know otherwise, do a rabbi a favor and keep it to yourself.

Assuming this is a true myth, why did Reb Simcha Bunim repeat it to his students? What does this story tell us about the journeys of our feet as well as the journeys of our souls?

The 20th century religious studies scholar Mircea Eliade remarked on this story that the truest treasure “is never so far…it is buried in the most intimate corners of our houses…behind the stove in the center of life…[it’s] the warmth that dominates our existence in the heart of our hearts, if only we knew how to dig it up.”

But we must meet the moment, ready to dig. We must go on our heroic journey, venturing out into the world to meet the Other. The gold that lies just below our feet remains unreachable if we remain unprepared to uncover it.

As you sit here, you too are on a journey. Where would you situate yourself in this present moment? Are you in the Cracow of your mind, your safe home, dreaming of a better tomorrow? Are you waiting for your marching orders to pursue the next big thing? Have you been waiting weeks, years, or decades for your chance to dig? Have you boarded the donkey cart headed home to seek the comfort of family and community during this holiday season? Are you hoping for any dream at all, wanting an external force to orient you toward a new direction? Or maybe you are at the end, having found your treasure chest and struggling to share its bounty with those you love.

When Reb Simcha Bunem told and retold this story, he helped his students see that at whatever stage they were at in their narrative, they knew where it would end. They knew that not only would they venture out, but also one day they would return home - transformed by the journey, to reconnect with their Briendels and friends. It's easy to forget when we are filled with passion and overcome by the vividness of our dreams. We often neglect our families, our Jewish communities, and care for our bodies. Still they remain home waiting for us. When Reb Simcha Bunem repeated this story over and over, he was teaching us not to identify so strongly with our life-stage, that we forget the truth. The gold we all most truly need remains under our own hearths. Through his repetition, he helped his students see through the excitement of the present and to touch something timeless.

Wherever you are in your journey, what would it feel like for you too to take a break from it? Whether you saw yourself in that story rushing to Prague or high-tailing it back to Cracow, on Yom Kippur we have the unique opportunity to take a breath in the timelessness of our tradition. Tonight, we join together for Kol Nidrei and declare that all of our promises to self and others are null and void. We set down our identities, projects, and conflicts that have tied us up all year. All that we owe. Everything that we believe we deserve. We set it all down. As a community, we will pause from fulfilling physical needs like eating and wearing pleasurable clothing, take a break from our work in the world, and turn off the autoplay Netflix stream of our life.

Over the next 25 hours, we step out of the well-worn paths and roles that can sometimes constrain us and deny much-needed growth.

How can we turn from our stories? Our narratives of the way that we are, must be, should be? Can we step back and observe our journeys from a different, more empathic, perspective? Do our journeys serve us? Do we like where these roads lead?

In pausing, we can return to our world anew. We can reflect on the part of ourselves that runs hither and thither, not noticing the sparkling gold below our humble floorboards or the gentle, loving laughter of our own partner when she hears our latest scheme.

Our tradition gives us clues to what matters most. The Mishnah, our oldest rabbinic wisdom text, calls Yom Kippur one of the happiest days of the year. What could this mean? Yom Kippur is a chance to lay down our emptiness, our guilt, our drivenness, and find refuge in the knowledge that forgiveness is not only possible, but real. What if we live in a world where G!d forgives? Where our loved ones accept us as we are, set aside the physical and emotional debts, and move together toward something new. The gold of our lives might be just under our hearth, the heart of every shtetl house. Are we ready to find it?

Yom Kippur is more than just happy. It is also called the Sabbath of all Sabbaths. Tomorrow in the Haftarah we will hear Isaiah 58:13:

If you refrain from trampling the Sabbath, from pursuing your desires on my holy day, and call the Sabbath a delight and the holy day of God honorable; if you honor it, not going your own ways, or seeking your own pleasure, or talking idly; then you will find your joy in God, and I will cause you to ride in triumph on the heights of the land and to feast on the inheritance of your father Jacob." The mouth of God has spoken.

Shabbat literally means rest. It's the day when we rest pleasurably in the knowledge that we actually are enough. We call the day a “taste of the world to come” because it is our weekly dose of transcendence and bliss that we achieve not at the end of our story, but each week when we stop and breathe.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel writes:

He who wants to enter the holiness of the day must first lay down the profanity of clattering commerce, of being yoked to toil…Six days a week we wrestle with the world, wringing profit from the earth…The world has our hands, but our soul belongs to Someone Else. Six days a week we seek to dominate the world, on the seventh day we try to dominate the self.

And yet, resting on Shabbat is more than simply recharging one’s batteries to return to the grind when the work week begins anew. Shabbat is a day that sustains life in more than a physical sense. It’s not just about increasing efficiency and being able to make more widgets on Sunday because we rested on Saturday.

Yom Kippur is called a Sabbath of Sabbaths. We not only differentiate ourselves from the clattering of commerce, but also from the rancor of our own personal drives. We have 364 other days to walk our paths. But this one day a year, no matter where we find ourselves we take a break from eating, drinking, physical intimacy, and the comfort of nice clothes. There we can offer rest to our most essential part, our soul. If Shabbat is a taste of the world that is coming, Yom Kippur is when we sit and have three meals. The mystics teach that we have a special soul inside of each of us that awakens only on Yom Kippur. This soul is called Yechidah - Unity consciousness and it offers us the ability to see beyond time and space.

I have a gift for you and it’s better than a pot of gold. At this moment, there is nothing to do. You have already been forgiven. We might even playfully translate Yom Kippur rather than the Day of Atonement but the day of At One Ment. Even when tomorrow’s sun sets and the day ends, we can still grip our identities and stories a bit less tightly. In remembering what it was like to get off the hamster wheel, even when we climb back on, we do so with a wink and a knowing smile. We have known something else.

Sometimes after really taking a day off, we realize that we don’t want to return to certain stories, habits, roles, or relationships. Through distance and differentiation, we glimpse that we don’t like where we are. Our tradition insists that today’s insights can transform our stuckness and pivot our lives to another story.

Yom Kippur is our grand opportunity to embrace ourselves in a new way. We need not wait until we return home to Krakow to find forgiveness, enoughness, and love under our floorboards. All of these possibilities are here on the doorstep of a new year. May letting go into this Yom Kippur bring us a year of newness, love, health, and potential. Shanah tovah!